Pain Studies (A Kinder Place)

Sam Davis

See it On Campus: Level 1

Visitor InfoLibby Leshgold Gallery

Award Recipient

Landon Mackenzie Graduation Award for Visual Arts – Honourable Mention

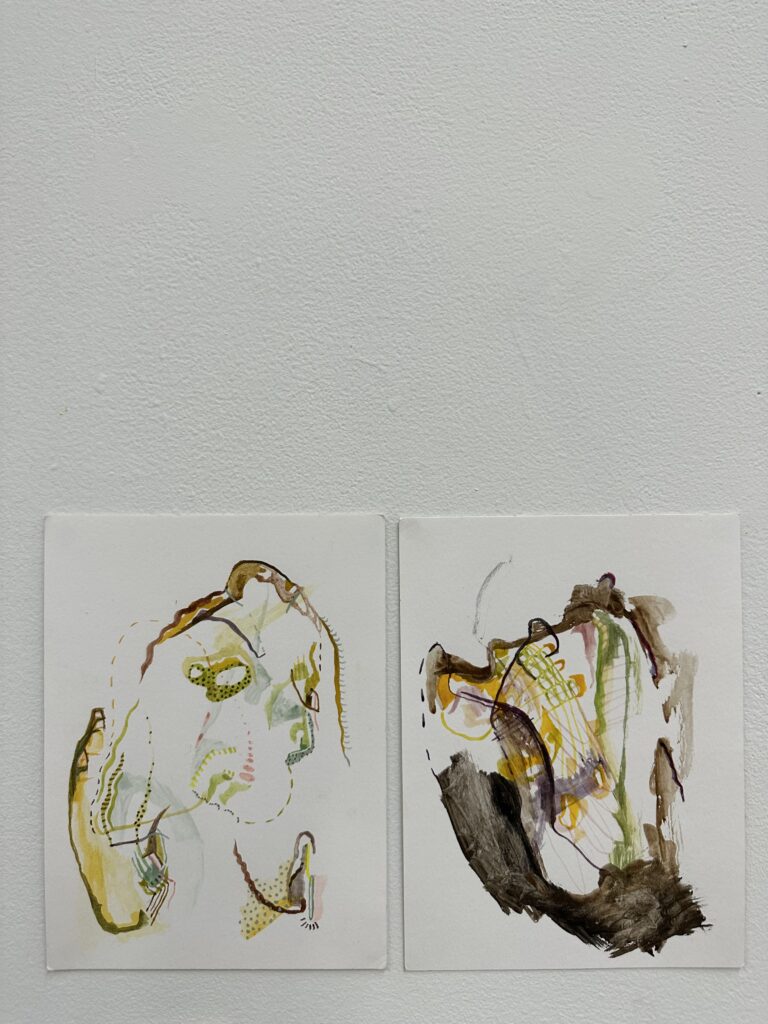

Pain Studies (A Kinder Place) is an emergent durational exhibition that took place in Emily Carr University’s Michael O’Brian Exhibition Commons over the course of 27 days during my thesis exhibition. Exploring the merging of physical and psychological spaces through the blurring of internal and external worlds, this exhibition worked to consider the chronically ill body spatially. Having spent my time time within the MFA program conducting pain studies, investigating the symptoms of my chronic pain and illness through art-making, the archive that has been created over the two years is the physical manifestation of time spent with the sensations of my internal world. These artworks tell stories of different moments with and in pain, map the shifting and changing terrains of my painscape, and communicated the overwhelm of living within chronic pain and illness through their multitude. Housing the furniture, objects, and pain management devices from my bedroom, 115 drawings, 250 photographs,150 screenshot cell phone notes, and 12 bread-based sculptures created during my time at Emily Carr, as well as my own physical body, I occupied the space for the duration of the month. Struggling to curate a single exhibition from my archive of pain studies that reflected the fluidity of an ever-changing painscape, allowing the installation to remain in motion provided the opportunity to depict the multifaceted nature of chronic pain. Treating the week provided on either end for the installation and de-installation of the work as part of the show itself, I was able to expand the two-week show into a month, allowing for twenty different iterations to take place during that time.

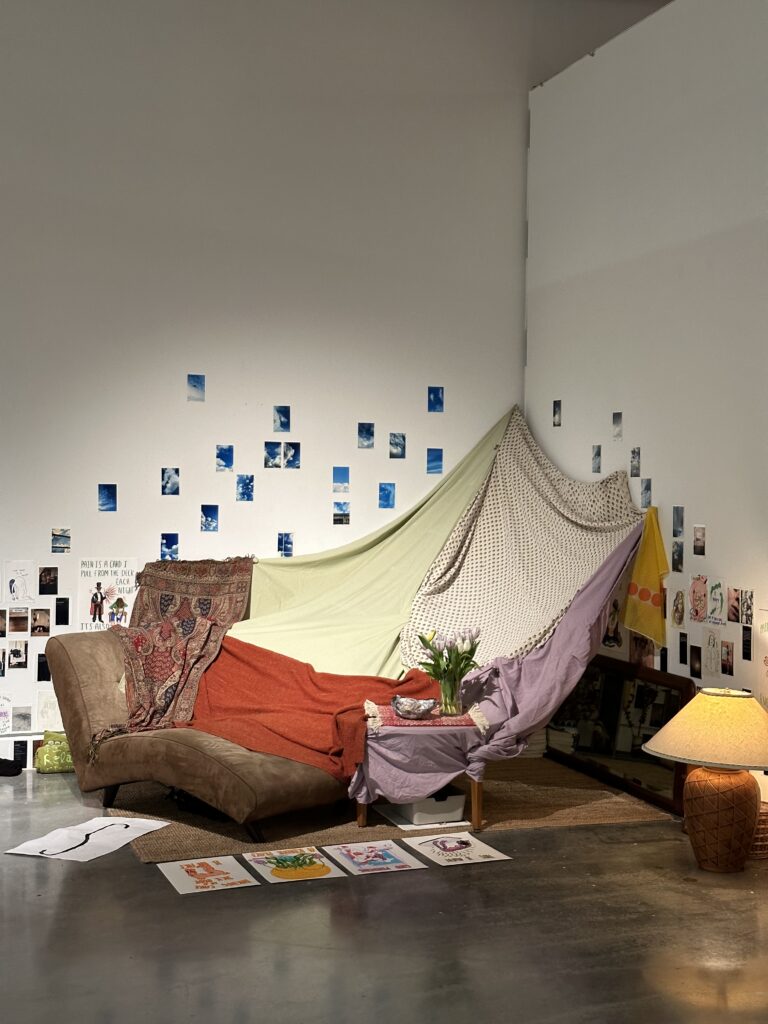

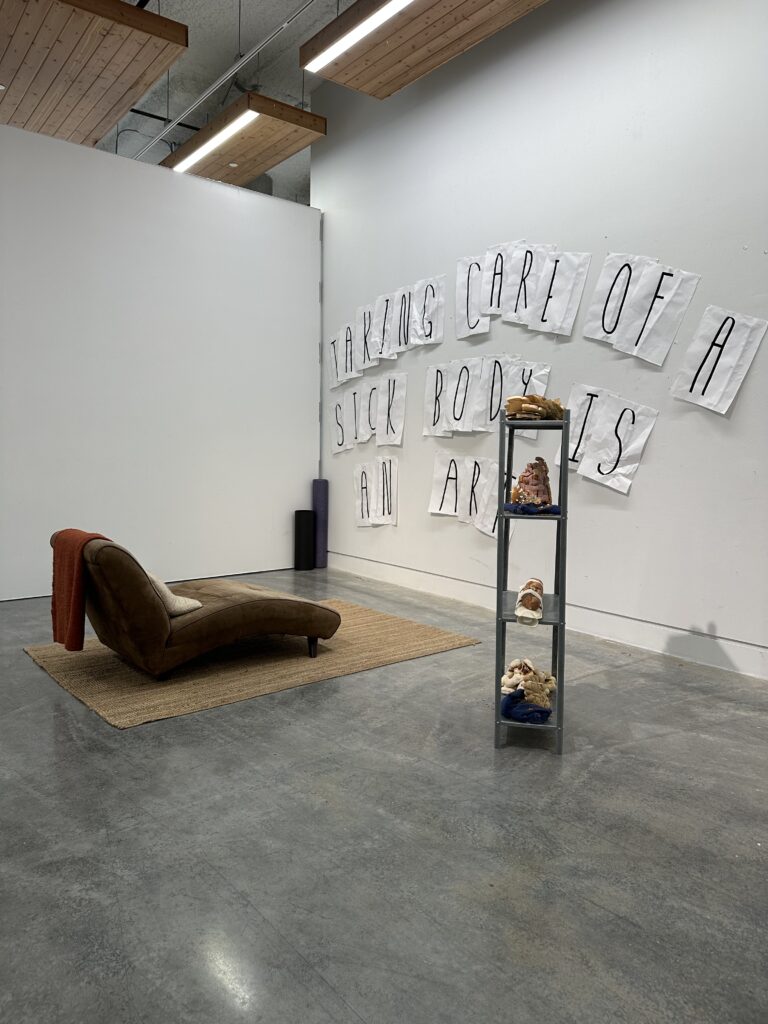

Having housed the vast majority of the practices and artworks produced over the course of my two years in grad school, it felt appropriate to begin the exhibition with the recreation of my bedroom space. Aside from my bed, the show began with the transportation and reconfiguration of all of the furniture, objects and pain management devices that made up the contents of my room. Centred within the gallery, a room comprised of one long wall and two small side walls, the space resembled a set, stage, or diorama.

Utilizing the exhibition as an opportunity for practice, I worked in an emergent way, curating the artworks into different configurations in an attempt to communicate both my experiences as a person living with chronic illness and pain, as well as the processes that I have been engaged in while conducting pain studies. Using sticky tack to hang the various drawings, photographs and notes, I was able to efficiently install and take down the various components as I worked.

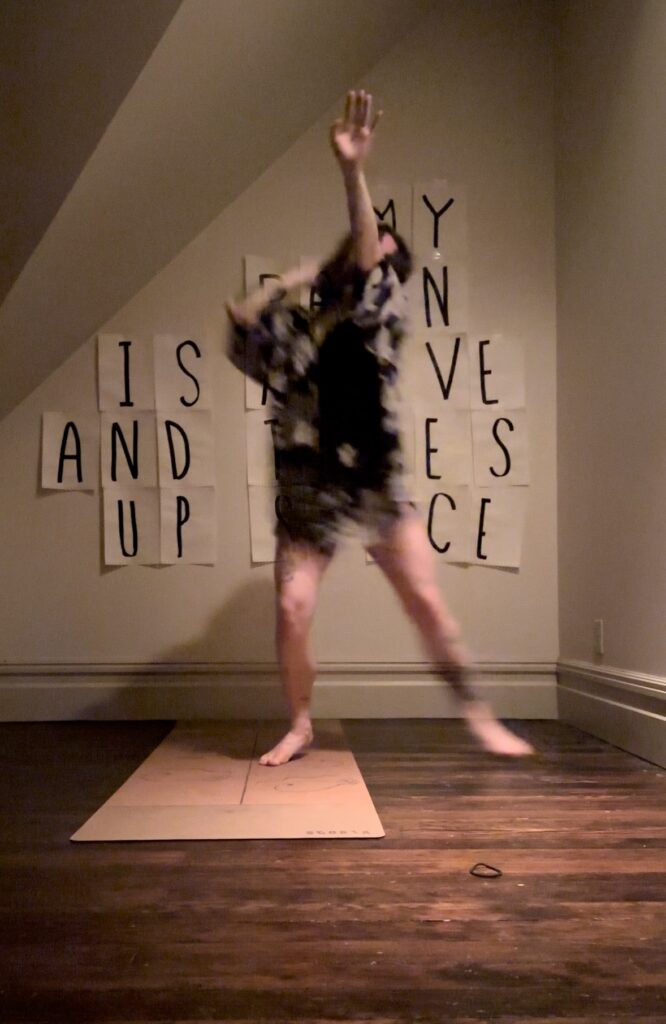

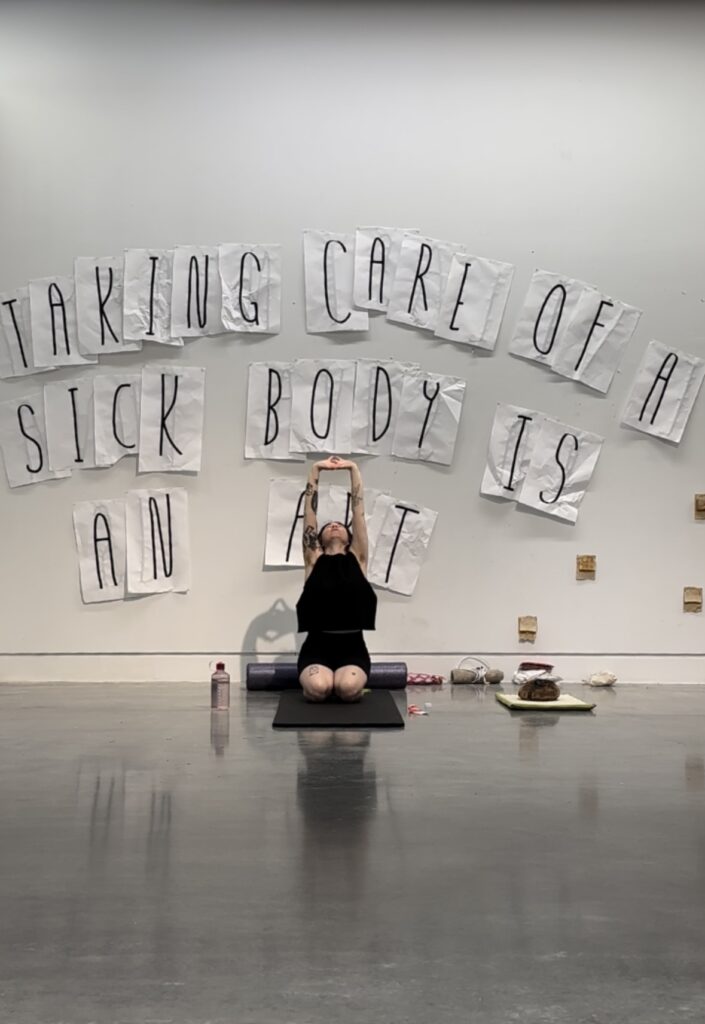

During the exhibition, I exercised the care-based rituals of stretching, movement and dancing that previously took place within the privacy of my bedroom walls. Despite the presence of a viewer, I chose to frame these actions for myself as practicing publicly as opposed to performing for those watching, thus maintaining the function of each action as a pain management tool within my greater practice. Now on display for the public to view, these practices were both an act of vulnerability and defiance; an invitation to bear witness to the intimate processes required to care for a body with pain and an assertion that caring for a sick body need not be hidden from the public gaze.

As the work required long hours spent standing on concrete within the gallery, it was crucial that I maintained these practices to help mitigate the impact that I felt within my body. Having pushed past my limits following the first week of the show, upon reflection, I developed a daily routine to ensure the exhibition remained physically sustainable.

Beginning each day, I went for a walk, collecting my thoughts on the actions of the day prior, while easing my body back into motion. A period of reflection, these walks provided space to begin responding to the public engagement I had observed the previous day. Writing in my phone’s notes app, I reflected on what each iteration was communicating and which elements needed to be introduced, modified or rearranged in order to convey that day’s intended message. From there, I sat by the ocean, allowing myself to slow. As so much of this process was dependent on fast-paced intuitive decision-making, it was important to grant myself opportunities to be still. Despite seeming small, this proved to be one of the most valuable practices I engaged with during the exhibition for it provided pause, both of body and mind, prior to returning to the gallery space. On the days that it was raining and this practice was not possible, I found it took me longer to settle back into my work.

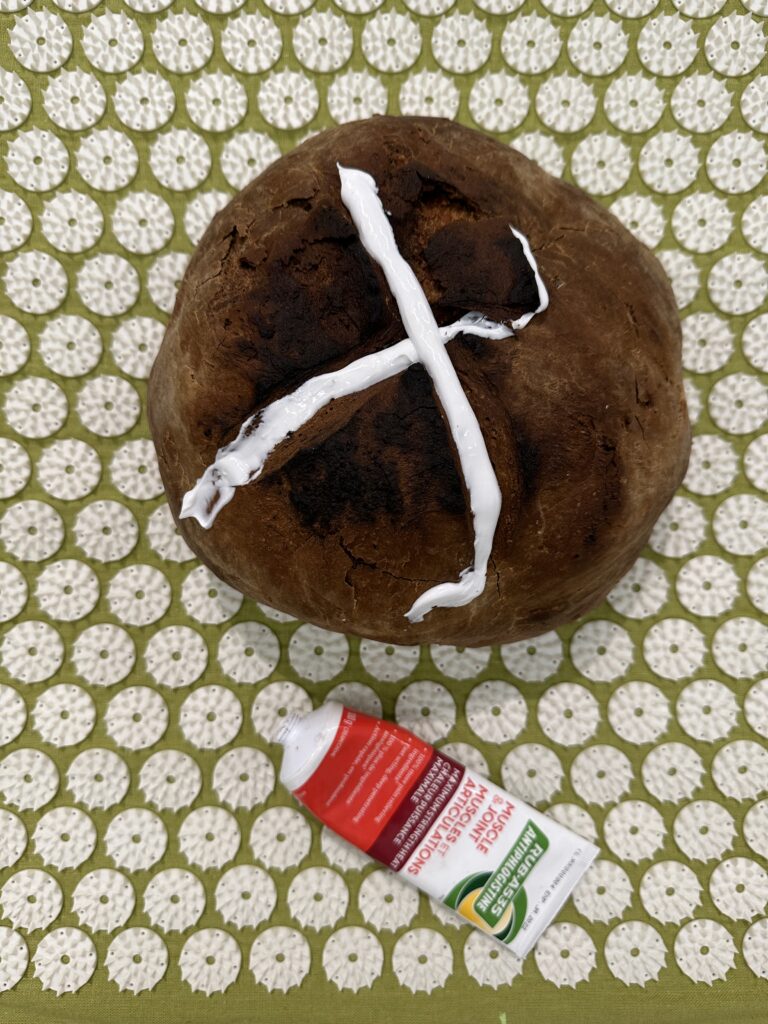

Upon arriving in the gallery, I would begin engaging in my intuitive stretching practice, allowing my body to dictate the types and successions of movements that it required. Massaging rub A535 onto my sore muscles, a scent distinctly associated with bodily aches, I infused the smell of pain into the gallery space. Often lasting for an hour or two, this stretching practice was fundamental in reversing some of the pain and stiffness that my body held from the day(s) prior. Again, a period of reflection and sustained slowness, my time spent stretching in the exhibition allowed me to inhabit the previous day’s installation, formulating a plan for the next iteration while simultaneously settling back into practicing within the public eye.

Once complete, I would finally begin working on that day’s installation. Throughout the duration of the exhibition, the furniture remained a tether to the literal physical space. Moving around the gallery, different configurations told different stories. At times, the furniture arrangement resembled the actual layout of my bedroom that it was referencing. At other moments, it was restricted, forced onto the footprint of the carpet mimicking the way that pain seizes or laid on its side, contained below hip height, the part of my body that was currently giving me the most trouble. I saw the furniture as the backbone to the rest of the work, it became the set that I inhabited while practicing things like dancing and stretching, created an environment for the photographs, notes, drawings, and bread sculptures to engage with, and was an anchor to comfort as the intensity of pain built.

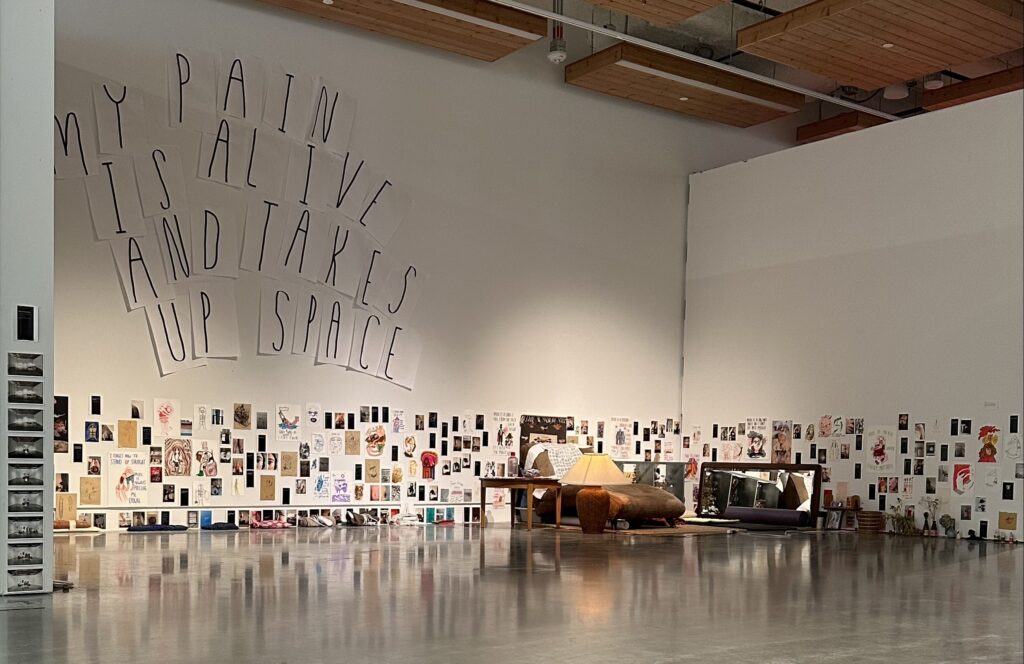

Upon initially bringing my furniture into the space, I was met with the immediate response of, “Wow, cute apartment!” from those viewing the work. Despite continuously adding elements over the course of the first week that upon closer investigation would have signalled that the work was about pain, I was struck by its continual invisibility. Drawings depicting my body within pain’s contortions, photographs and notes tracking its ever-changing frequencies, watercolour lines and shapes mapping the terrains of my internal world, these pain studies built and still, people stopped to take selfies in the mirror, posed on the chaise lounge, smiled and laughed with their friends, and carried on. This was intriguing to me as it mimicked the isolation that I have often felt when dealing with an invisible illness. I began exploring installation strategies to see what it would take to clue viewers in on what the show was about; expanding and contracting the different elements of the exhibition, laying the mirror on its side in front of my yoga mat to force those looking to take photographs in its reflection to lay down as well, and finally, building up to the moment where the entire collection of my pain studies hung on the wall together.

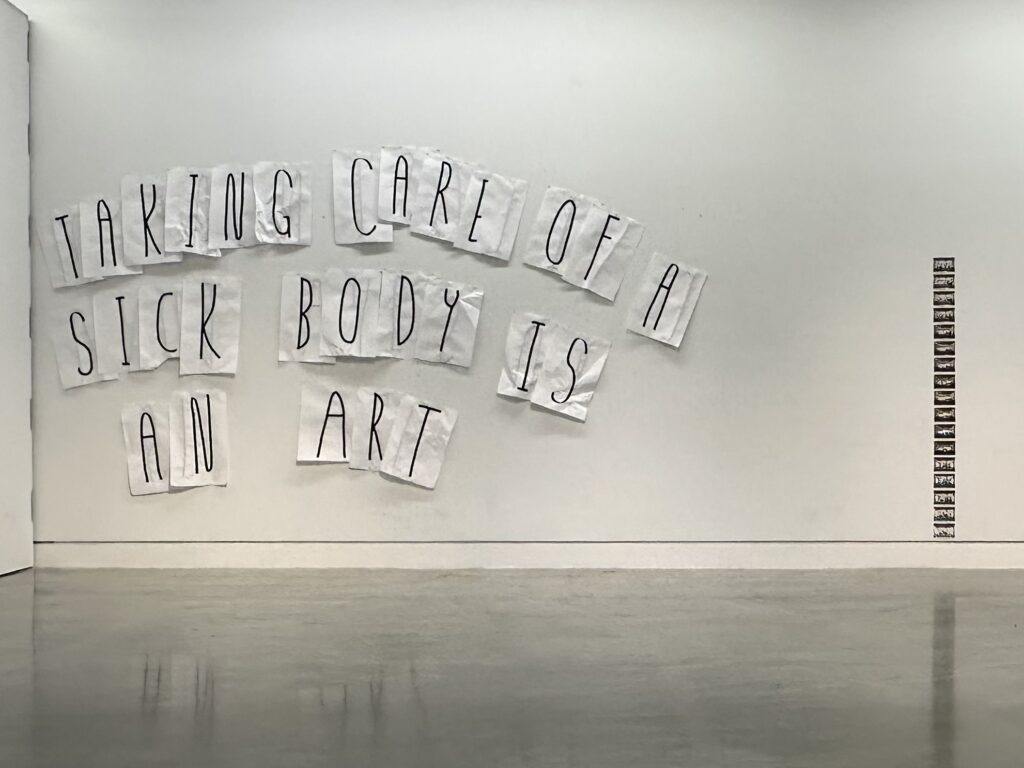

It was at this point of having installed the entirety of my pain studies that I observed a shift in the way that viewers began to interact with the work. Paired with a set of large-scale lettered posters reading “My Pain is Alive and Takes up Space,” I watched as my audience began engaging with the work on a micro level, no longer simply taking in the composition as a whole. It was here, on the eleventh iteration of the show, with my pain literally lining the walls of the space that I inhabited, that the invisibility of pain seemed to shatter and with it, space was made for moments of connection.

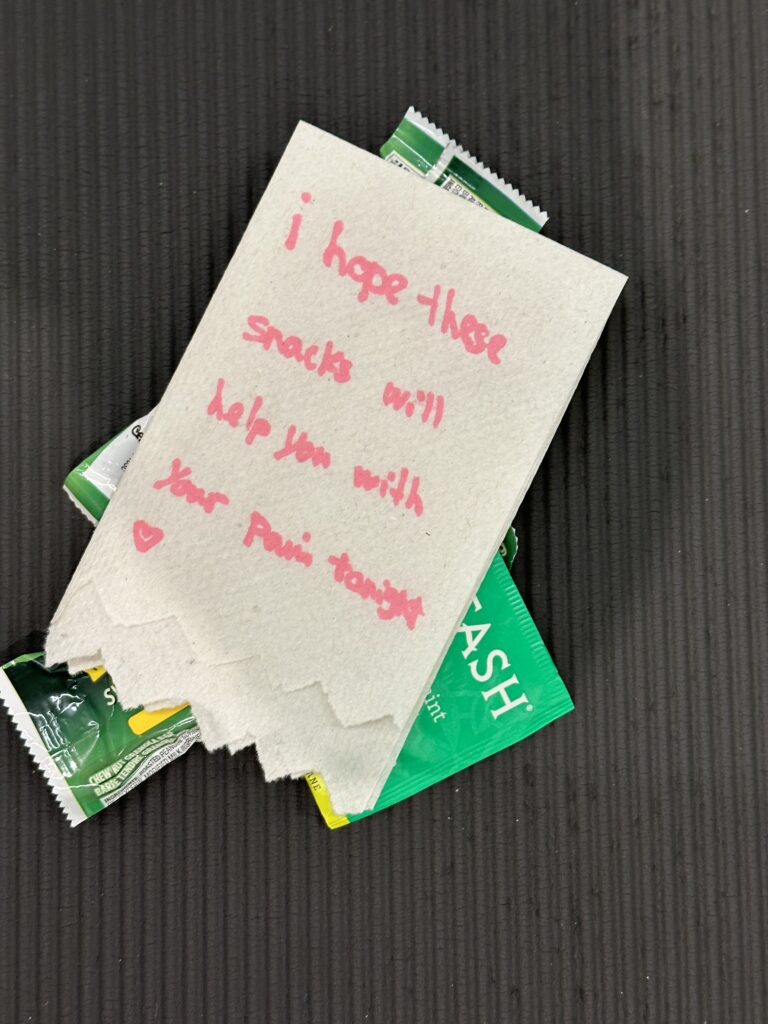

Leading up to the exhibition, I was unsure about whether or not to engage with my viewers as they moved through the space. As I rejected the notion of performance and opted instead for that of practicing publicly, it felt natural to respond to those seeking discussion around the work. It was through these conversations that some of the most meaningful moments of my time spent in the gallery emerged. Conversations around pain, loss, illness and grief are rarely had between strangers, yet through creating a space to offer mine to the public, I was met with theirs in return. It was in these moments of connective communication that I was reminded of art’s ability to position us to one another. To be seen in my pain, and to have others feel seen in theirs meant the work had done its job.

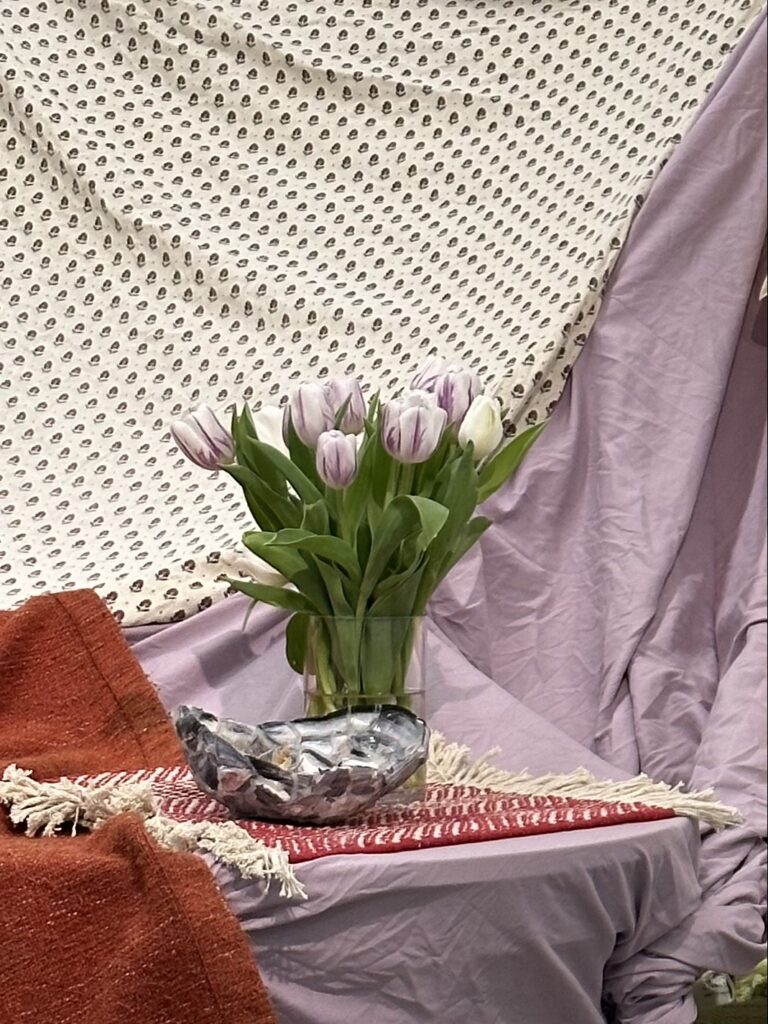

At the halfway point of the show, I began introducing elements that spoke to the second portion of the exhibition’s title, A Kinder Place. As the twelfth iteration, I built a blanket fort around the furniture tucked into the corner of the gallery; a hideout from pain. Over the course of the next few days, I spent time drawing, playing ukulele and singing, reading and napping within the privacy that it offered. On the fourteenth day, I hung a series of photographs of clouds and blue skies surrounding the fort, a disruption expanding beyond the line of pain studies still hung at hip height. A signal of optimism, it was through these simple actions that I hoped to suggest that even in the depths of pain, reprieve could be found.

Upon completing the day’s iteration, I ended each session of work with dancing. Whether in the gallery space or in my now empty bedroom, intuitive movement once again served as an opportunity to reconnect with my body and slow down. An outlet for emotional expression, at times these dances were joyous, a celebration of all of the things my body is capable of. Other times, however, following the movement my body asked for led to the release of stored pain.

On one of the evenings, while dancing particularly hard within the gallery, I was flooded with emotion and instinctually began ripping at the lettered posters reading “My Pain is Alive and Takes up Space” before ending up in a heap, crying on the gallery floor. Taken off guard by my display of raw and unfiltered pain, I took a moment to compose myself before looking up at the wall which now read, “My Pain is Alive.” The poignancy of this residual phrase, left following an unplanned burst of emotive action, was one of many moments that encouraged me to continue allowing myself to be guided by gut-based embodied knowledge. In lacking the time to question whether or not these types of actions were correct, and instead, trusting that I could reflect and respond to the conditions as they changed, at times, it was as though the work was alive and I was the tool that it emerged though.

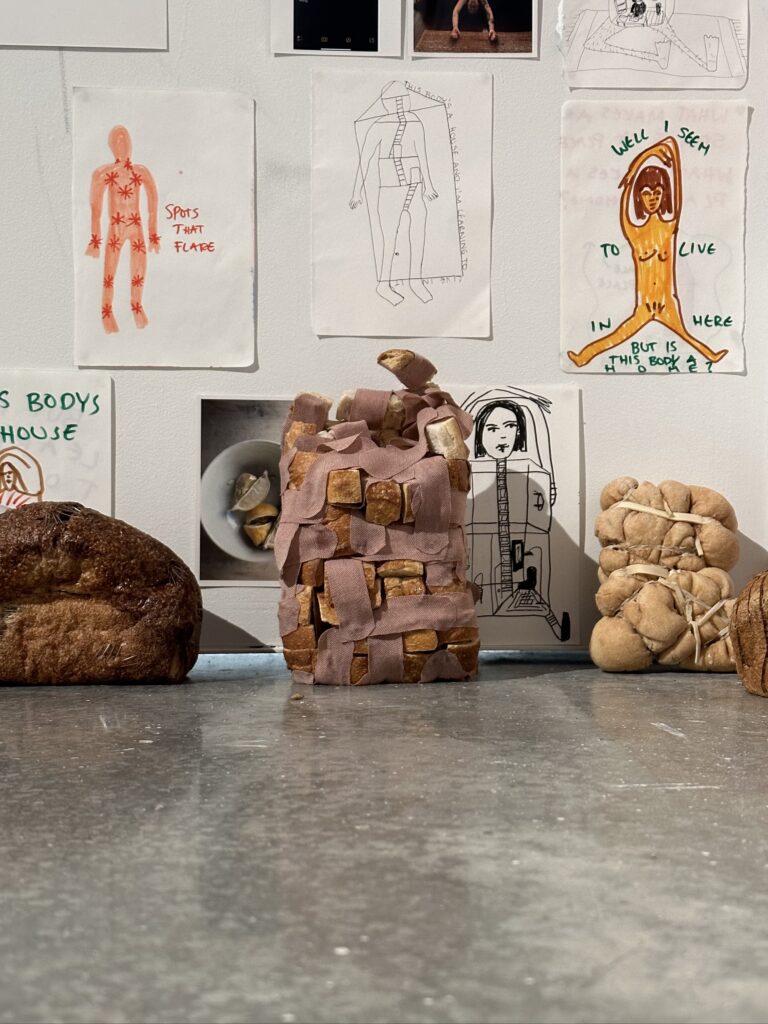

During the final days of the show, I introduced my bread-based sculptures, creating a third rendition of my reoccurring exhibition, Help or Hinder Hard to Say. Now more than a year and a half old, some of the pieces crumbling, brittle and worn out, the bread rested amongst equally tired pain management devices. Burnt-out heating pads and torn wheat bags with their scorched kernels from countless microwave sessions spilled and resting, they lay, supported by the furniture they inhabited in their working days.

Once posed upon white plinths, sat within the stark, clean cube of the gallery, this third iteration of the work offered comfort to tired forms as they adorned the domestic space they now found them-selves in. A brittle, thread-mended loaf sat centred on the coffee table, resting between two bouquets of tulips in varied stages of decay. Under the warm glow of my bedroom lamp, surrounded by fallen petals, this composition served as a reminder; despite the care that we provide, clinging to the idea of preservation is an unattainable and needless goal.

This notion of breaking down as a point of potential, a reoccurring theme seen through many lenses within the entirety of my thesis exhibition, once again offers the opportunity for metamorphosis as a resistance to the impulse to cling to things as they once were. Whether the building up of drawings to be torn down the next day to express a new idea, bread as a medium that all but promises to decay, the corners of drawings, now slightly crumpled and less pristine than when they entered the gallery or the wear now present on my furniture, returned to my room upon the completion of the exhibition, these things tell the stories of an event, a life, of something that once happened. A residual trade-off to have lived in motion, perhaps the value of the work lives in its recognition of its own temporality.

In one final moment of serendipity, upon wanting to create a second set of lettered posters reading, “Taking Care of a Sick Body is an Art,” I realized that the phrase contained the exact amount of letters as its predecessor, “My Pain is Alive and Takes up Space.” Flipping over the now crumpled and torn posters, I drew out the new letters on the reverse side. Hung beside a column of nineteen photographs of the previous iterations that took place within the space, this final instalment of Pain Studies (A Kinder Place) was the meta-reflection of both the work that had taken place within the gallery over the course of the month as well as the development of a sustainable art practice that I had been engaged over the two years prior.

It is not an exaggeration to say that embarking on the process of creating this lived art practice has transformed my relationship with pain. In acknowledging the care required to maintain my health as an art in and of itself, it has granted me the freedom to dissolve the illusion of perceived stagnancy within a diagnosis of chronic. Instead, my journey with health remains in motion. No longer seeking an arrival, I work instead, to build a kinder place. One of many, perpetual in motion, inside and outside of myself, the work is never finished. In letting art be the tool used to direct my living, I continue to move, in the general direction of forward.