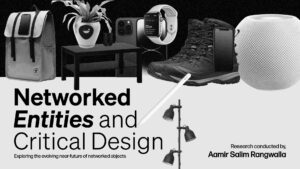

Reimagining Rituals: Design’s role in amplifying cultural IdentityReimagining Rituals

Leea Nadeer Contractor

See it On Campus: Level 2

Visitor InfoAward Recipient

WA Architects Ltd Master of Design Graduation Award – Honourable Mention

My research focuses on the Parsi diaspora, its disengagement with tradition, its lack of access to and its desire to conduct and participate in their cultural rituals. Employing the methods of autoethnography, participatory research, and cultural-centred design, my research explores the cultural practices of the Parsi community to understand the current role that rituals play in their lives and the barriers to performing these rituals.

I discovered evidence of the community’s desire to make the steps behind Parsi rituals and their significance more accessible. I focused on developing a digital application (app) to express and explore responses to my research findings. This app serves as a repository and almanack that will allow community members to access rituals and traditions by disseminating information about how the rituals are conducted, the materials used, and the events and beliefs upon which they are based.

I was born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan as a member of the Zoroastrian community known as Parsis. This has left an indelible impact on my work as a Designer.

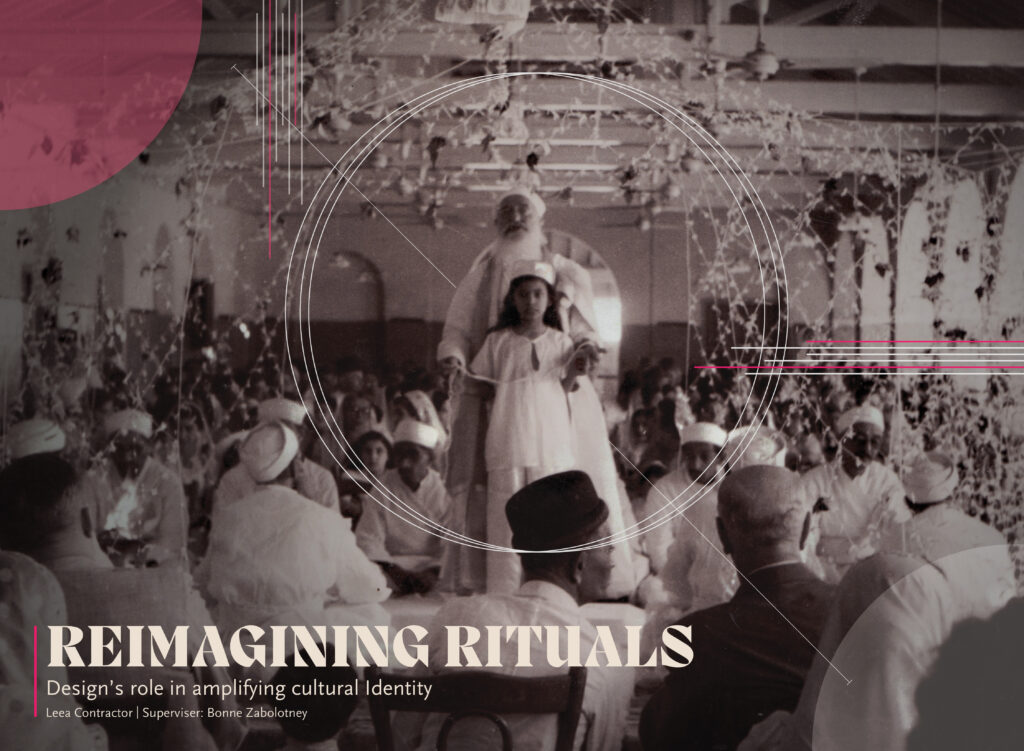

I have always been curious about Design’s role in amplifying and preserving our Ethno-religious Culture and Identity. During my undergraduate thesis, I used the idea of Food as a means of preserving our culture.

This culminated in a website called Jamjoji, which translates to ‘please eat’. Jamjoji wove food and narratives together, acting as a virtual scrapbook for Parsi recipes, and the stories that go with them.

As I began the Master’s program at Emily Carr University, I imagined my research to be a natural extension of my undergraduate work. However, while the general area of inquiry stayed the same, my trajectory soon shifted away from food.

Over the past two years, I can pinpoint three pivotal milestones that shaped my exploration,

and defined the path my research would take.

Navroze 2022, The World Zoroastrian Congress and finally the act of designing my app, Reimagining Rituals.

I began my research by conducting a rapid sketching and word association exercise with members of my cohort.

Here, I prompted them to generate eight distinct ideas of what culture and community meant to them.

To my surprise, despite the diversity of the group, most of the responses contained drawings of significant cultural rituals, which led to in-depth discussions about these rituals and their significance.

It was around March 2022, when I began exploring the importance of rituals to an individual’s cultural identity.

Navroze, the Persian New Year, was around the corner. It occurs on the spring equinox and is widely celebrated by cultures from around the world, including mine. While preparing for it, I felt more homesick than I had since moving to Vancouver, because I knew it would not be the same as it was back home.

I remember how my family would come together to celebrate. There would be the smell of roses from garlands; Intricate chalk designs outside each door, the delicious food, and the elaborate Haft Sheen table on display.

My sister and I tried to recreate it as best we could.

There were several frantic phone calls to my mother asking: what we needed, what we could substitute, and brainstorming where we could find specific items. For example, we had to make a last-minute run to Jugo Juice in an attempt to buy sprouted wheatgrass on Navroze morning.

For the first time, I was not a passive participant but the person carrying out the ritual, and despite our best efforts, it was not the same. I still felt extremely disconnected from my culture and my home. It was this feeling that I then chose to counter with my research. Not just by unpacking the role of rituals, but the Significance they hold for individuals of a diaspora.

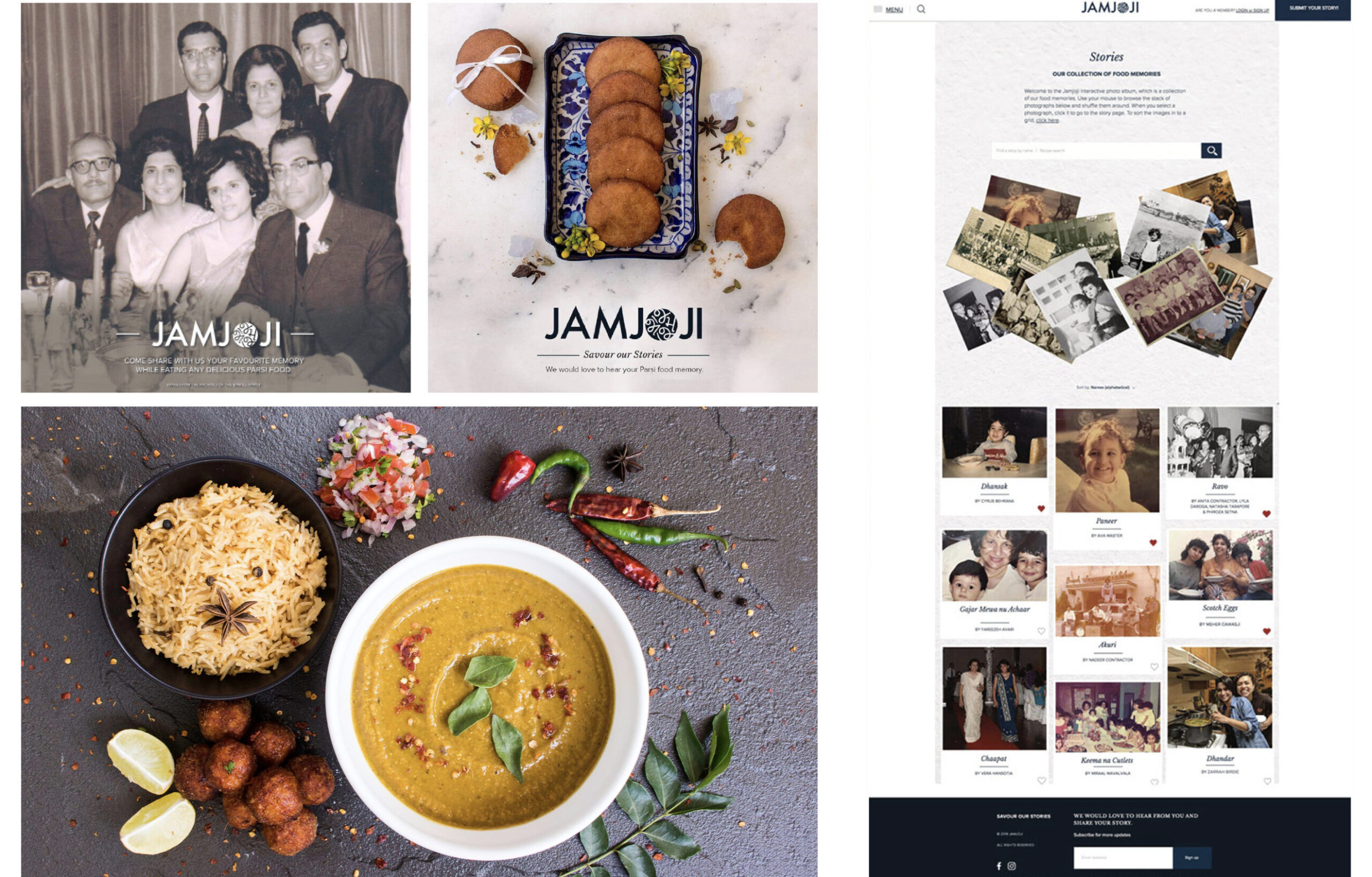

The approach I took for this thesis can be divided into two main spheres: auto-ethnography and Culture-Centred Design.

This led me to discover that many Parsi youth are unable to conduct rituals because of their lack of access to knowledge about the steps to take.

And so began my journey into exploring multiple ways of dispensing the knowledge and information to them.

Using these research methods, I was able to construct a framework that reflects my lived experiences and the experiences of members of my community.

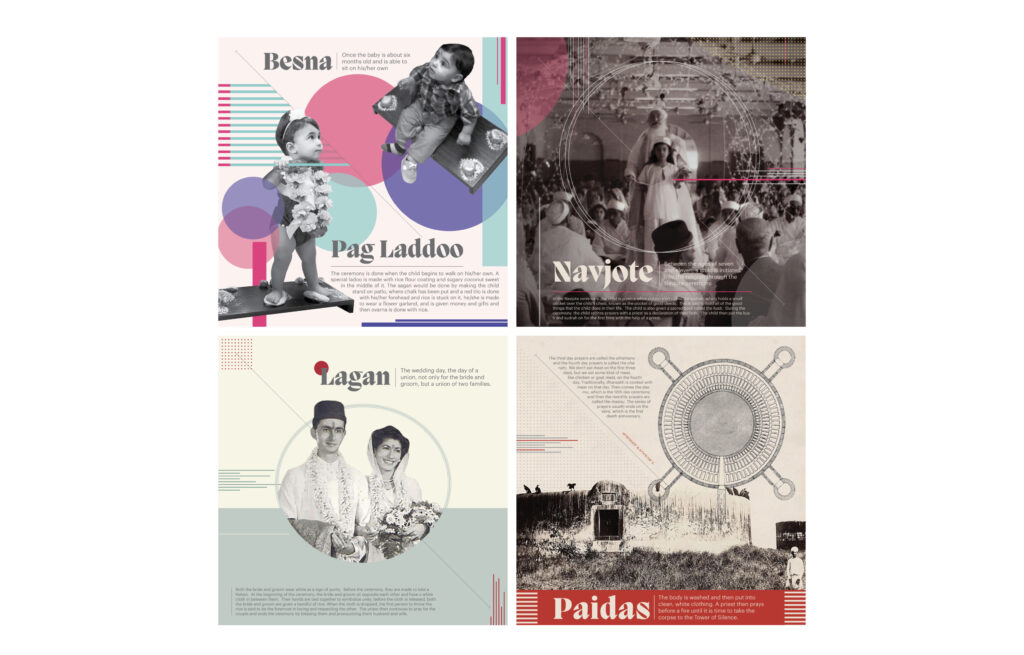

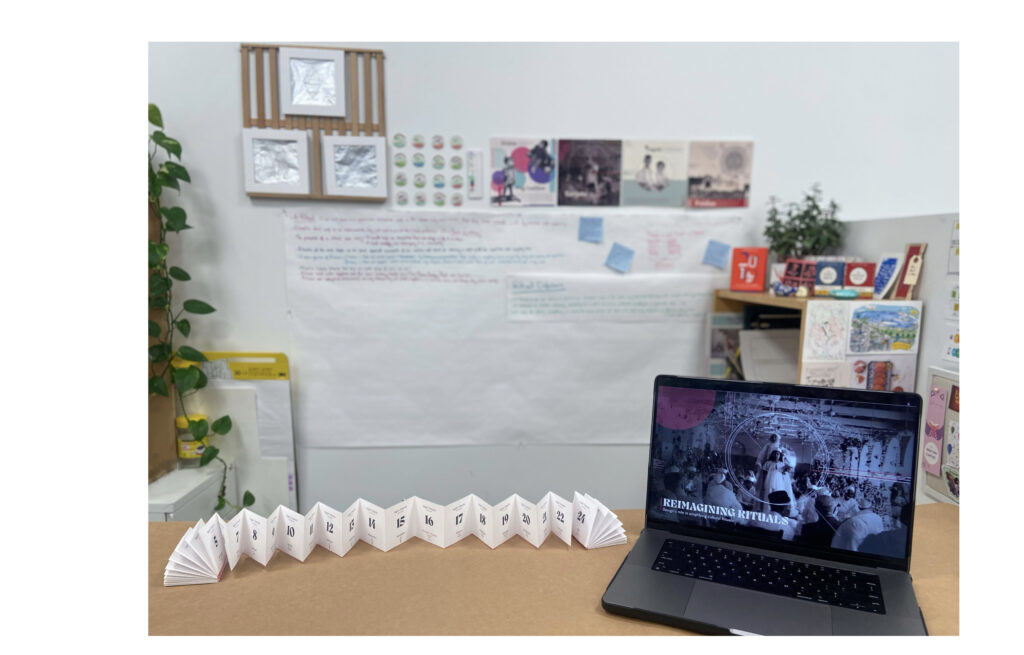

The Parsi Pack explored ways of disseminating information through a culturally rooted, tactile experience,

The Lifetime project did so through the graphic representation of various rituals,

The Sticker Pack through spaces for virtual communication,

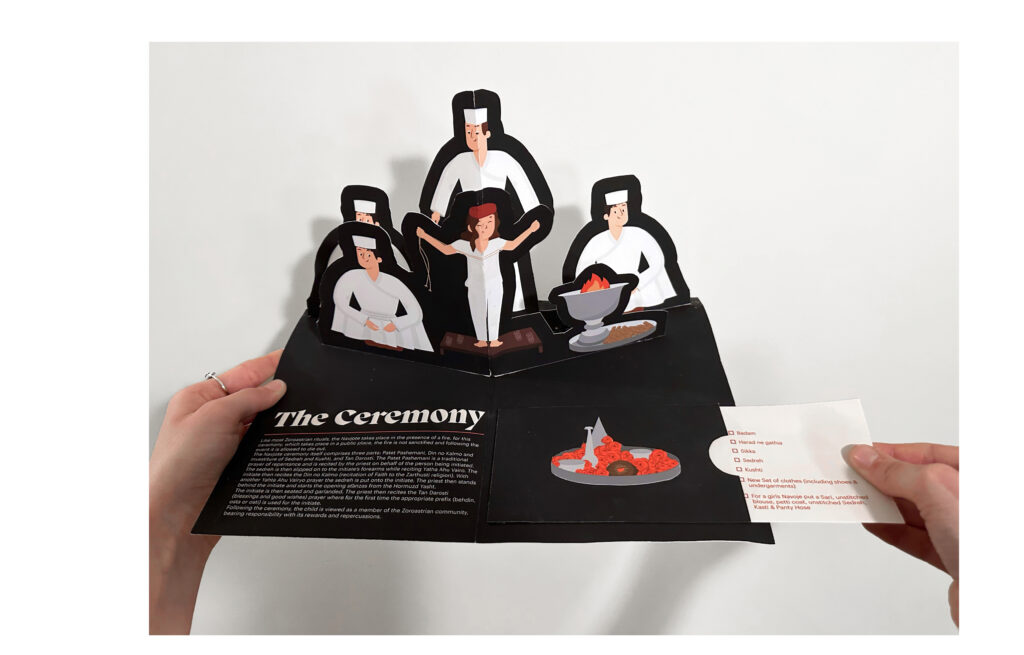

The Pop-up project through intergenerational learning,

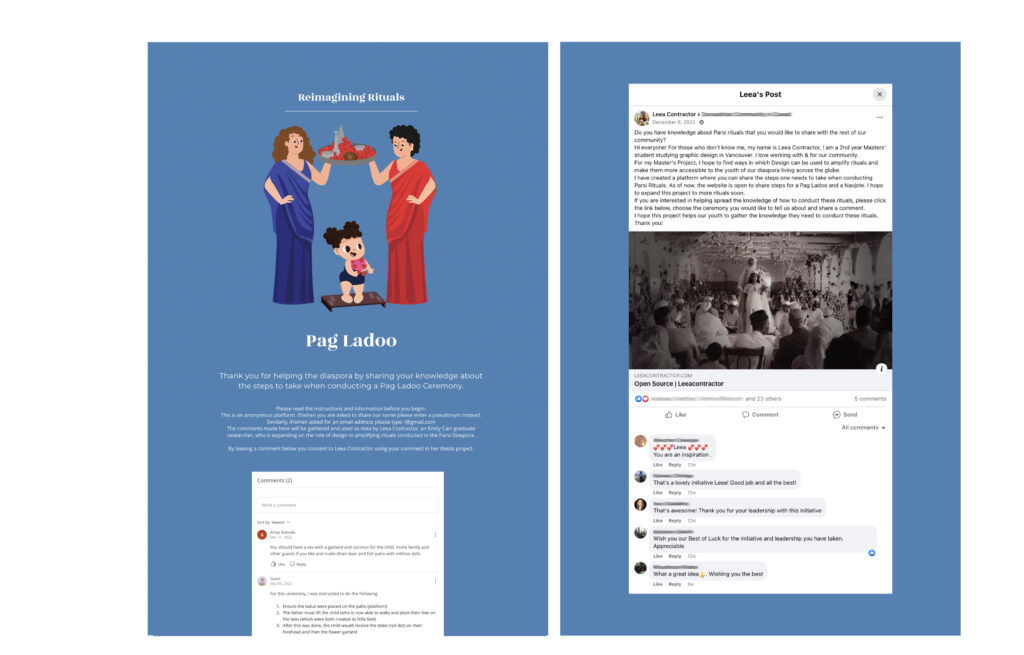

The Open Source through knowledge sharing on digital platforms,

And finally, dispensing information about rituals, through the creation of a calendar.

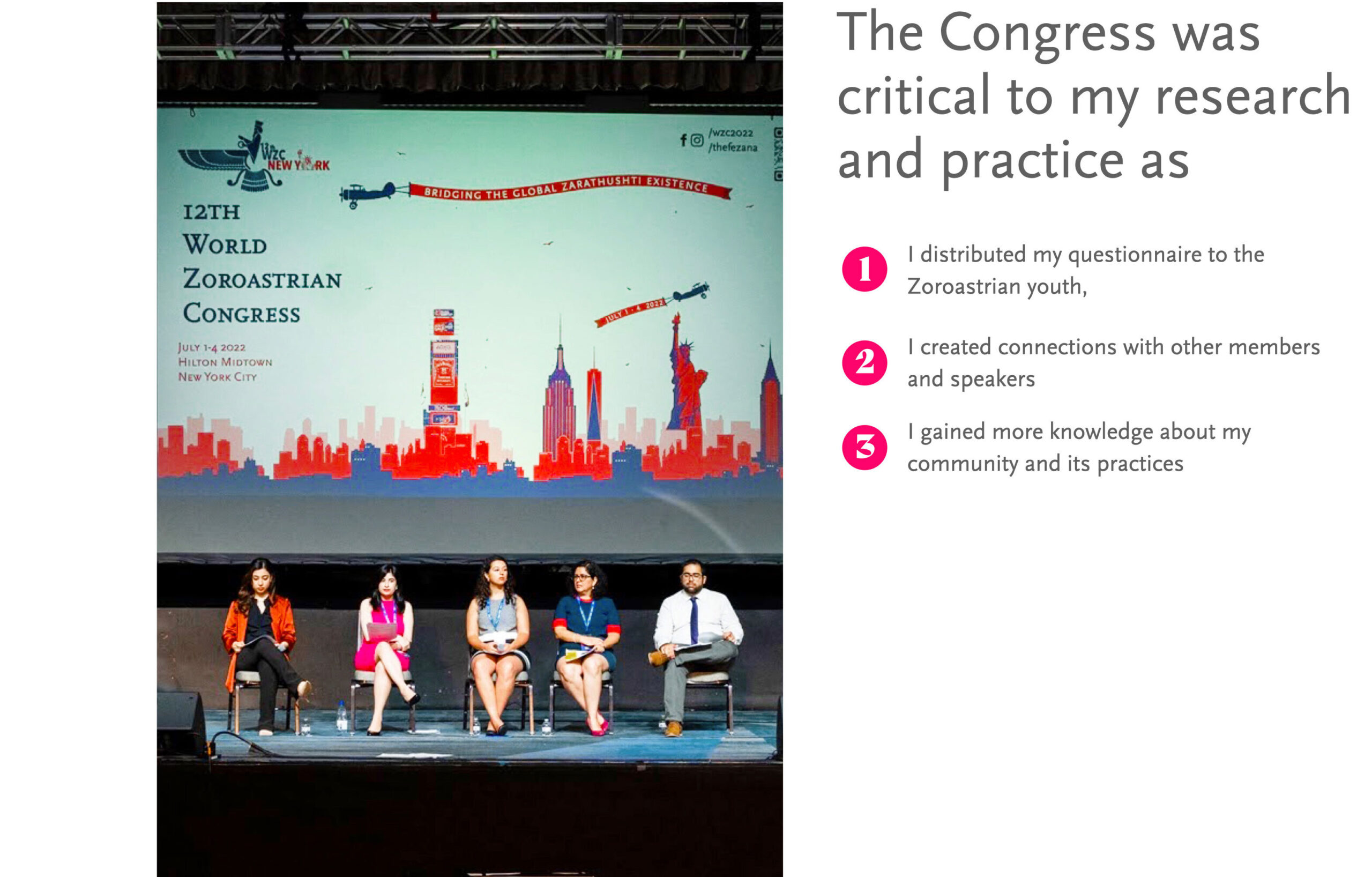

While Navroze 2022 began a ripple effect of observation, introspection and exploration, it was the World Zoroastrian Congress that propelled my research forward. It was held in July 2022 and was attended by nearly 12 hundred participants from around the world. These congresses occur once every 4 years, in an attempt to connect, teach and impart knowledge about our religion, culture and traditions.

I was brought on board as a part of their design team and was honoured to have been appointed committee chair member, along with several others. At the event, I also gave a talk to promote the Zoroastrian Return to Roots program, designed to strengthen community identity amongst Zoroastrian youth from across the world.

The Congress was critical to my research and practice as during this time:

I distributed my questionnaire to the Zoroastrian youth, I created connections with other members and speakers, and I gained more knowledge about my community and its practices through the talks, discussions and workshops.

The questionnaire I created was aimed at gauging my audience’s connections to Parsi rituals.

There were two main takeaways I gained from this.

The first was that: 49% of the participants portrayed a bleak outlook for what they thought the future of Parsi rituals would look like, using words such as ‘non-existent’, ’Diminishing’ and ‘Declining.

- The next major take-away, was that the youth of the Parsi diaspora continue to struggle with connecting to their community, culture and roots, mainly due to a lack of practicing key cultural rituals and the connection they forge to our identity.

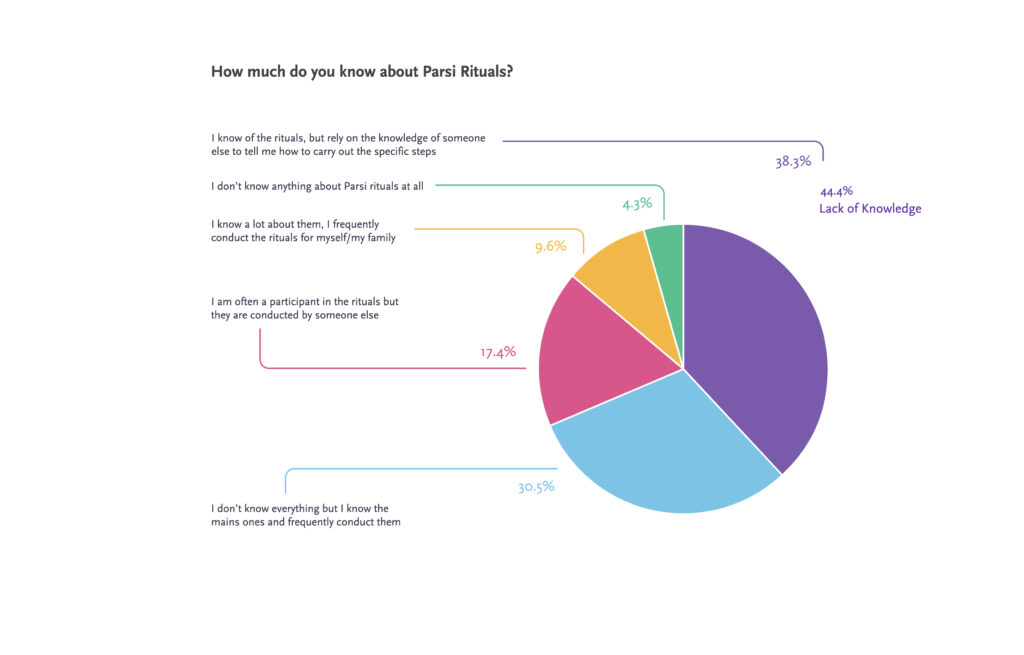

- This was seen when asked, how much they know about Parsi rituals, 38.3% of the respondents selected that they ‘Know of Parsi rituals but rely on the knowledge of someone else to tell them how to carry out the specific steps’. Of those 38.3%, a majority of the respondents, selected ‘lack of knowledge’ as the reason for this.

The data gathered through this method shows that the Parsi youth recognise that the future of our rituals is dwindling, as they lack the knowledge to conduct them, despite having a deep desire to do so.

This led me to host several Focus Groups sessions with my respondents. The key insights I gained from those sessions were:

- That there was a general feeling, of a lack of connection towards our rituals, because the participants, did not understand the background and significance of them.

- The participants agreed that the best way in which to receive knowledge about rituals was through a digital platform.

- And lastly, was the idea of adapting and adjusting to the country they now live in.

- They expressed that “The beauty of being Parsi is the ability to adapt our customs, rituals and traditions so that they continue to be relevant to our lives”.

This leads me to the final milestone of my thesis research. It took the shape of a mobile application: Reimagining Rituals. This was based on the findings from both my focus group sessions and, the insights gathered from the projects I designed and created.

Since access to information about rituals, was a significant concern for my participants, a mobile app mitigates the problem and takes advantage of a format, that is familiar to them.

The app has been designed so that the material available to the users can be personalised, accessed online and offline, and provides a convenient, self-directed learning experience.

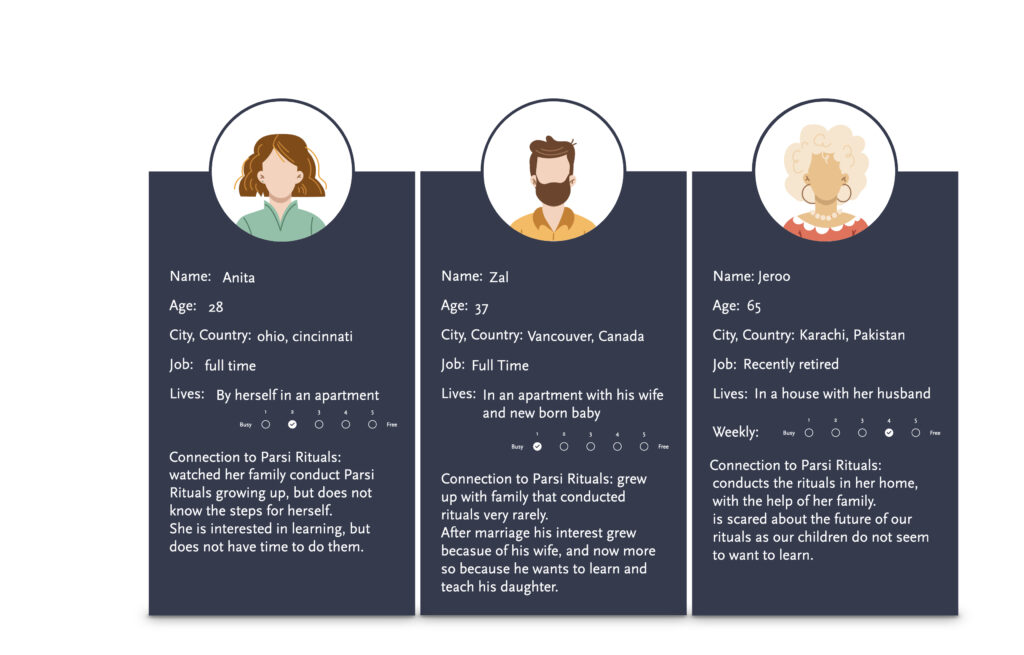

I began by creating three user personas: Anita, Zal, and Jeroo; which were based on the findings from my questionnaire and focus group sessions.

It was important to the development of my app that I considered a wide range of personas. Not only do they represent my target audience, such as Anita and Zal, who are both youth members and part of the second wave of Zoroastrian migration, but Jeroo, who is elder and part of the first wave. The intention behind this was to make sure these persona’s goals, aims, and characteristics represent the needs of the larger group of Parsi diaspora users.

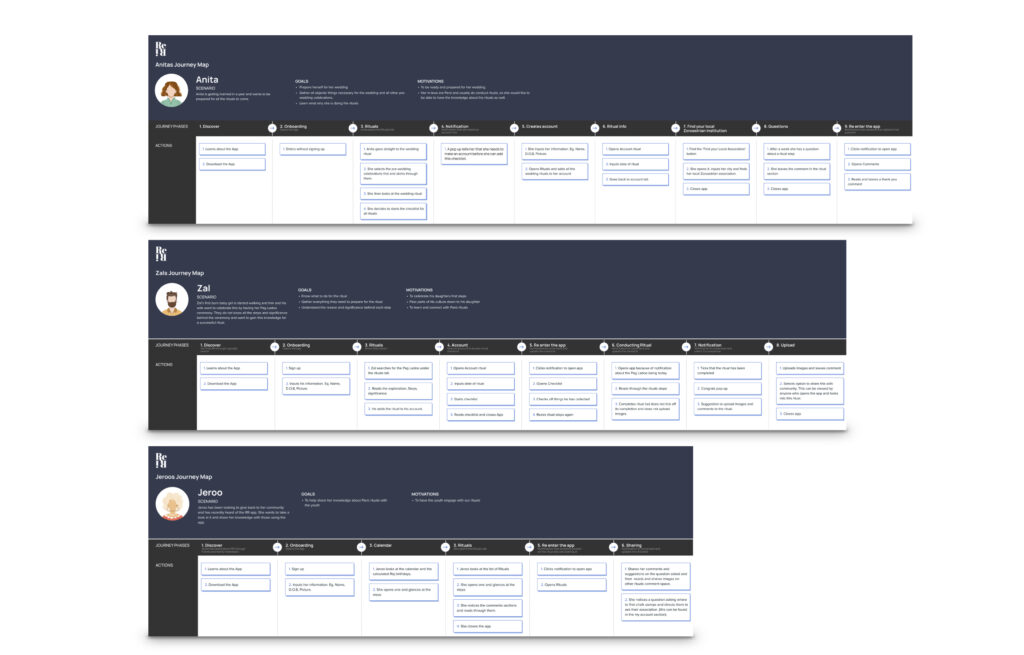

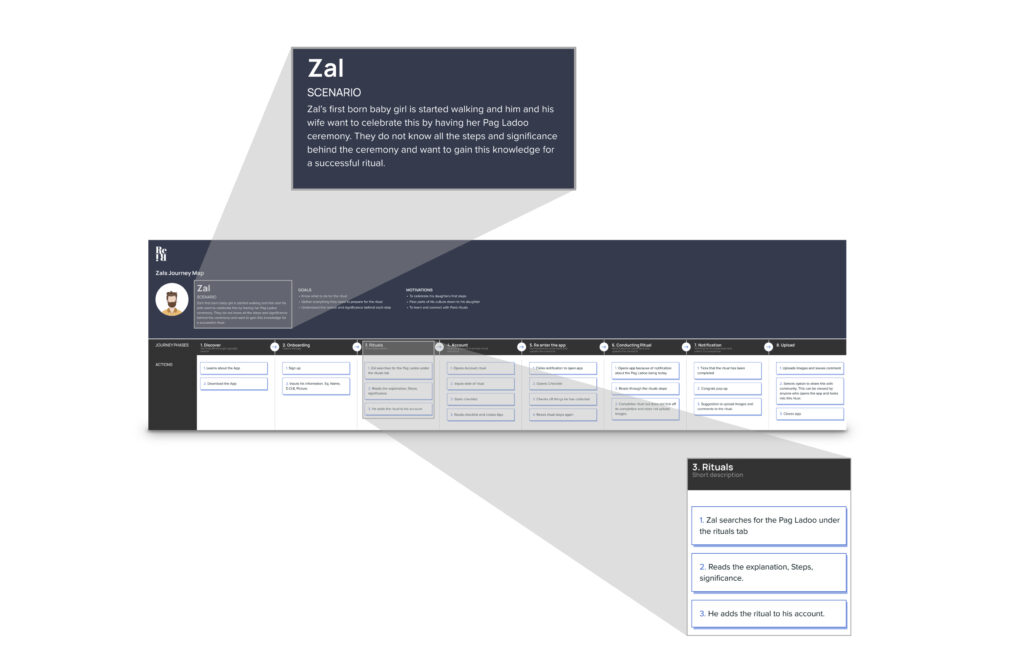

After building these personas, I created a user journey map for each of them to illustrate how each user would navigate through the app. These personas helped create a deeper understanding of my target audience including their expectations, concerns, and motivations, which in-turn formed

the bases of good user experience, and creating an app that would satisfy their needs

My research led me to create four main features for the app:

The First is the calendar. The Zoroastrian Shehenshai Calendar has 12 months of 30 days, plus an additional five days at the end of the year. Most of our re-occurring rituals are perfumed on a specific day or month; and we celebrate milestones such as birthdays and anniversaries according to both, the Shehenshai, as well as the Gregorian Calendar. When overlayed with the Gregorian calendar, this falls roughly one day further ahead every four years. It is interesting to note that families often maintain an Excel spread sheet to figure out such days. So a calendar that features both the Shehenshai and Gregorian days would not only be extremely useful to calculate these milestones but to identify upcoming rituals as well.

The next feature is the repository. This contains an extensive list of our rituals. These are both religious and cultural as well as re-occurring and once-in-a-lifetime events.

The next feature is the community. This exists so that the users of the app are able to connect with each other within a virtual space and continue to build a sense of community within the diaspora.

Lastly, the account section, which gathers all the users information

After I designed the app, it was time to design the branding.

The name of the app came almost naturally through my research.

Being a part of the diaspora means that with our changed environment and evolving identities, it has become necessary to, Re-imagine the nuances of how we conduct our rituals and how we disseminate knowledge and information pertaining to them.

For the logo, I wanted something that would feel familiar and yet new in its visual language.I started by using the Farohar, a commonly recognised symbol of our faith and community, and adapted and streamlined it to have a more modern feel.

I then took a typographic approach towards the idea of Reimagining Rituals and worked with the concept of reflection, adapting, and adjusting to create the logo.

After I created the app, it was time to design the logo. For the logo, I wanted something that would feel familiar and yet new in its visual language. I started by using the Farohar, a commonly recognised symbol of our faith and community, and adapted and streamlined it to have a more modern feel.

I then took a typographic approach towards the idea of Reimagining Rituals and worked with the concept of reflection, adapting, and adjusting to create the logo. I chose to use a deep red colour throughout the app. Red is seen as an auspicious colour in our culture, as it represents vitality, life and good health.

Through my research and the evolution of my design project, I gained a deeper understanding of rituals and the significance they hold. By Navrzoe 2023, I had come full circle.

Although my app is a prototype at this stage, I used certain mechanisms such as the calendar and checklist to better prepare myself this year.

I was able to remind myself to grow the Sabzeh two weeks in advance, gather all the elements needed for the Half Sheen table, and understand their significance far more than I had in the past.

I stayed in touch with a small community of friends and my sister, who lives in Arizona, to send each other

photographs and report on our progress in the days leading up to Navroze. Through this lo-fi, informal testing, and the initial responses I gathered from my app, I can imagine the potential impact Reimagining Rituals could have on my community by making our rituals more accessible to the youth of the Parsi Diaspora.

What started as an introspection on my relationship to Parsi rituals and their effects on my

connection to culture and community, has turned into a journey of cultural preservation, knowledge sharing and community building.

I hope this project acts as a framework for how technology and social media can facilitate cultural retention and amplification; and forge a deeper sense of belonging to our community.

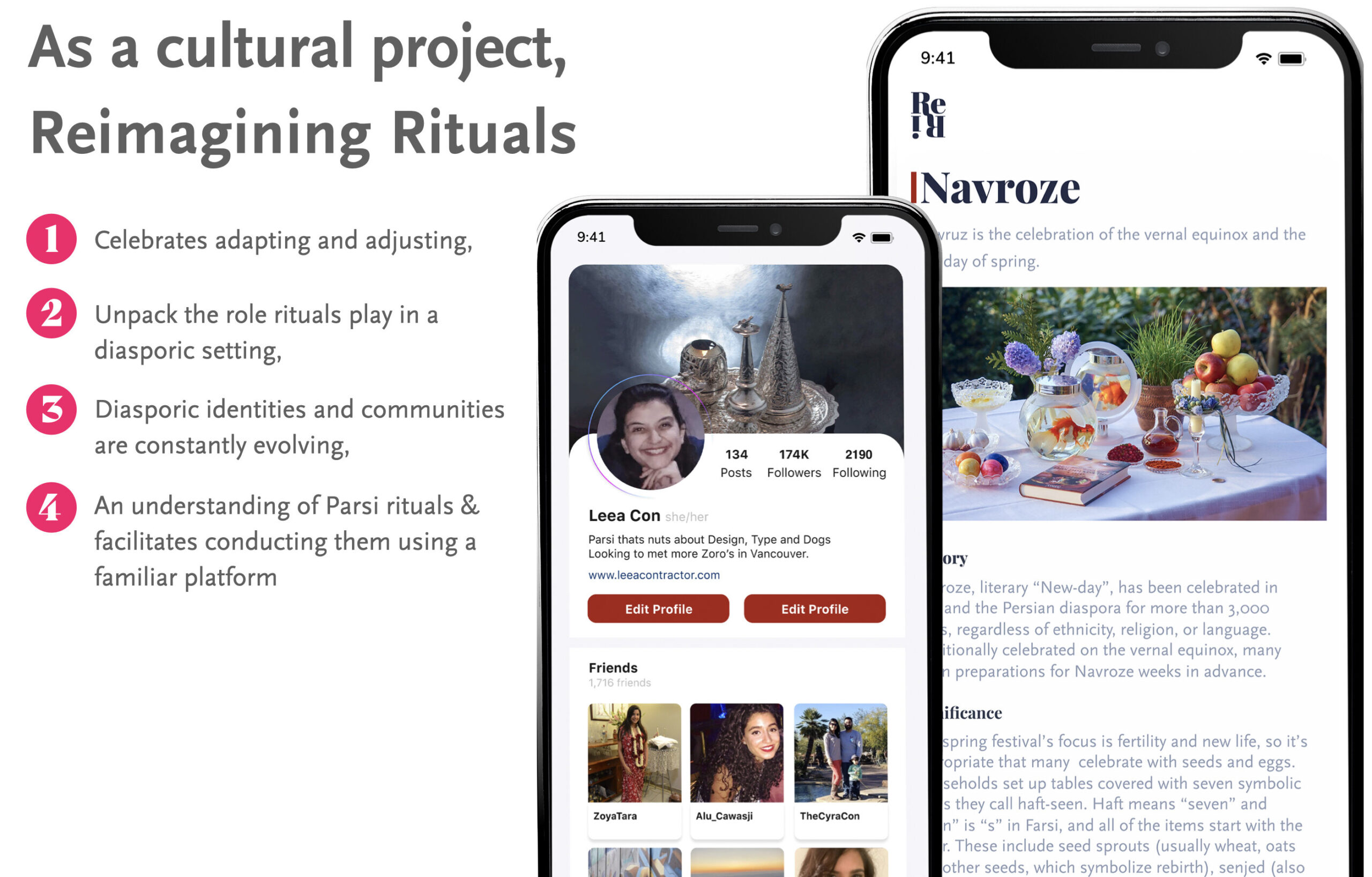

As a cultural project, Reimagining Rituals acknowledges the desire the youth of the Parsi diaspora have to connect to their community and does so by making the act of performing rituals easy to understand and carry out.

As a proof of concept this app:

- Celebrates adapting and adjusting to where you live to allow our culture to survive and thrive through these waves of migration.

- It attempts to unpack the role rituals play in a diasporic setting.

- It recognises the notion that diasporic identities and communities are not rigid, but instead, they are constantly evolving.

- Reimagining Rituals supports an understanding of Parsi rituals and facilitates conducting them using a familiar platform. This increases availability and access while remaining sensitive to tradition.

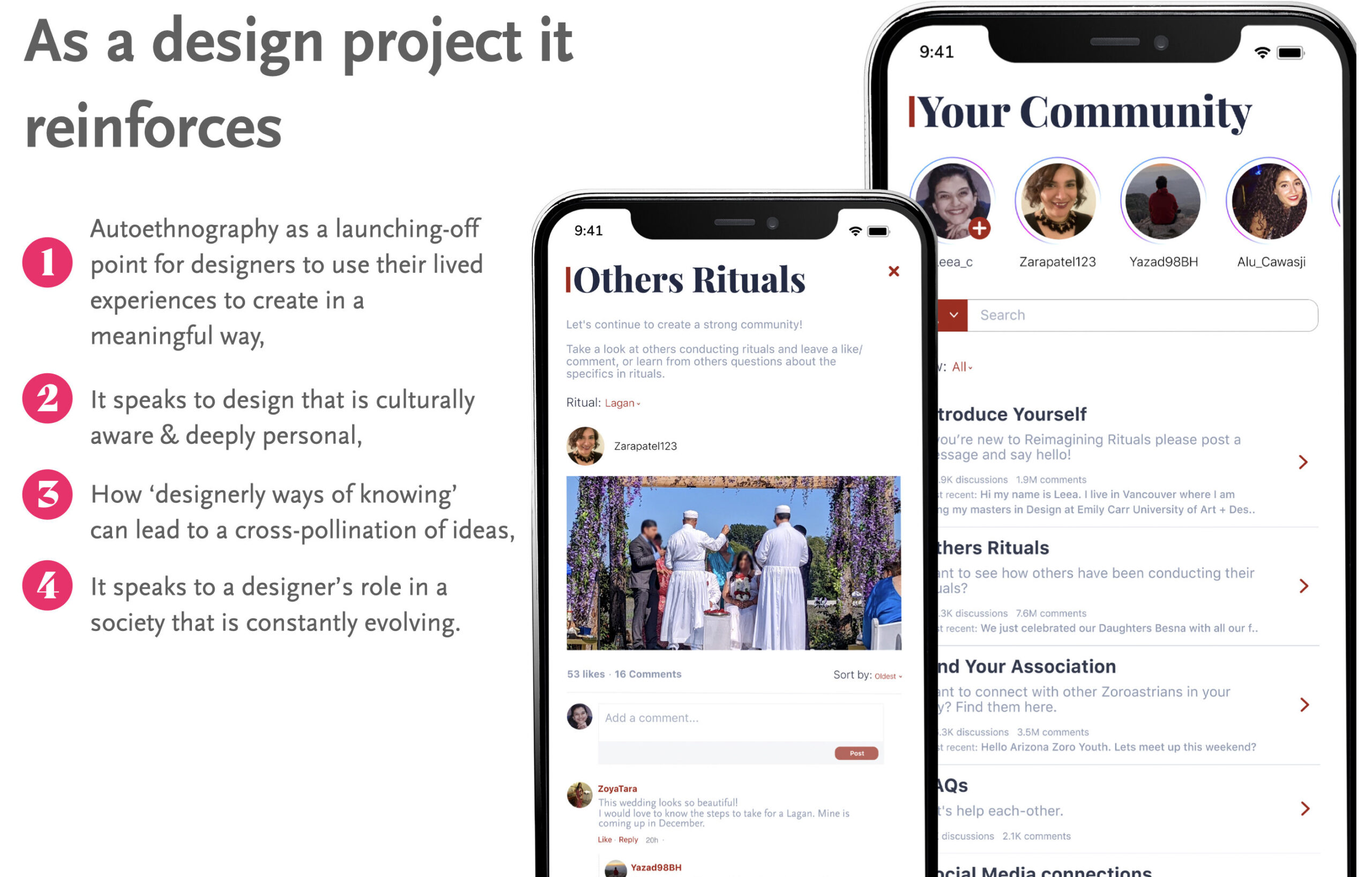

As a design project, it reinforces:

- autoethnography as a launching-off point for designers to use their lived experiences to create in a meaningful way.

- It speaks to design that is culturally aware & deeply personal

- It speaks of how ‘designerly ways of knowing’ can lead to a cross-pollination of ideas when the designer relinquishes the role of ‘expert’ and functions more like a facilitator.

- Above all, it speaks to a designer’s role in a society that is constantly evolving.